3.4 - Modeling Direction / Orientation¶

Location tells us where something is in relationship to a global origin and a set of coordinate system axes. The orientation of objects is equally important. Is an object facing north or south, up or down, etc.? Direction can be either relative or absolute.

- Relative directions are in relationship to an object’s current location and orientation. For example, if a person is facing north, west is to their left and east is to their right. Directions such as left/right, forward/backward, and up/down are relative to an object’s current orientation.

- Absolute directions are relative to a fixed frame of reference and always point in the same direction, regardless of their location. Directions like north/south and east/west are examples of absolute direction. (We will ignore the problematic locations of the north and south poles for this discussion!)

There are many ways to represent direction, including various combinations of distances and angles, and we could go through a discussion similar to the previous lesson on location to develop some of the various ways. But let’s just jump to the standard representation for direction - vectors. Vectors use a similar notation to Cartesian coordinates - distances along lines of reference. In fact, vectors and locations are often confused, so we need to spend some time differentiating between them.

Vectors¶

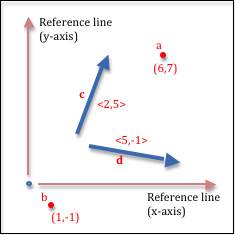

| A vector can be visually represented as a line with an arrow on one end. Vectors represent direction, so the arrow is important. The arrow points in the direction the vector represents. The end with no arrow is called the “tail”; the end with the arrow is called the “head.” A vector is defined by the change along each line of reference to get from the tail to the head. Therefore a vector is defined by two numbers: “how much x changes” and “how much y changes”. These values are often referred to as “delta x” (or dx) and “delta y” (or dy), as shown in the example to the right. If you use two points to define a vector, the “delta x” and “delta y” values are calculated by subtracting the tail coordinates from the head coordinates, i.e., (head - tail). |  |

| Since the standard representation for a vector is two distances, and Cartesian Coordinates for a position in 2-dimensional space is two distances, position and direction is sometimes confused. To keep these ideas separate, the remainder of this textbook will represent vectors by placing the distances inside angle brackets, such as <2,5>, or in general, as <dx,dy> for 2-dimensional space. For 3-dimensional space a vector is represented using 3 offsets: <dx,dy,dz>. If we use variable names to represent points or vectors, we will use single letters such as a, b, or c to represent the points, while we will use bolded letters such as a, b, or c to represent the vectors. The picture to the right shows some example points and vectors. |  |

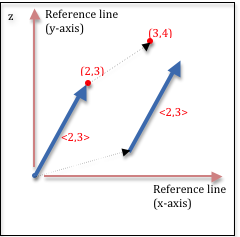

| A vector defined by a <dx,dy> representation has no position! Such a vector represents an absolute direction in relationship to its reference coordinate system. Let’s say that again. A vector defined by a <dx,dy> representation has a direction, but it has no position. Two vectors with the same <dx,dy> values are identical, regardless of how you might draw them visually. In the picture to the right, the 3 blue vectors are all identical. The green vector represents the same direction as the blue vectors, but it has a different length. A vector actually represents 2 things: a direction and a distance (or length). Its direction is indicated by the arrow at its head. Its distance is its length from its tail to its head. If a vector has a length of exactly 1 unit, it is called a unit vector. If a set of vectors have identical <dx,dy> values after they are converted to unit vectors, they all have the same direction. We will typically convert vectors to unit vectors because it simplifies the mathematical calculations that manipulate them and because it makes the representation of a particular direction unique. When you convert a vector to unit length, you are “normalizing” the vector since all vectors that point in the same direction have the same unit vector. So a normalized vector is the unique representation of a particular absolute direction. |  |

| If you want to represent relative directions using a vector, you need a vector and a specific tail location. A pair of values, (point, vector), represents a relative direction. For example, the point (2,3) and the vector <3,1> represents a relative direction from the specific location (2,3). |  |

Vectors vs. Points¶

| Notice that if a point in space is used to represent a direction from the origin, the point and vector are defined using identical distance values. (Examine the (2,3) point and the <2,3> vector in the diagram to the right.) However, this does not mean the point and vector are identical. The point is a single, unique location in space, while the vector is a direction. The major difference between points and vectors is that a point has a location while a vector does not. If you move a point its location has changed. If you move a vector you have not changed the vector in any way! Points and vectors represent different things and respond to manipulation in different ways. |  |

Vector Summary¶

- Direction is always relative to something!

- A vector represents an absolute direction in relationship to a frame of reference.

- A vector represents a relative direction when combined with a starting point.

- Computer graphics typically represents 2-dimensional vectors using two distances, <dx,dy> and 3-dimensional vectors using three distances, <dx,dy,dz>

- A vector represents both direction and distance.

- Making a vector have a length of one unit “normalizes” it into a unique representation for that direction.

- Vectors can’t be “moved” because they have no location!

WebGL Vectors¶

Vectors are used extensively for model representations and for describing the motion of objects in animations. They are represented by three component values, <dx, dy, dz>, using floating point numbers. This means a single vector requires 12 bytes of memory.

Manipulating Vectors¶

A vector can be manipulated to change its direction and its length. The following manipulations make physical sense:

- Rotate - to change a vector’s direction.

- Scale - to change a vector’s length.

- Normalize - to keep a vector’s direction unchanged, but make its length be 1 unit.

- Add two vectors. The result is a vector that represents a direction that is the sum of the originals.

- Subtract two vectors. The result is a vector that represents a direction that is the difference of the originals.

- Given a point, add a vector to it. The result is a new point that is in a new location.

- Given a point, subtract a vector from it. The result is a new point is in a new location.

- Given two vectors, calculate their dot-product, which calculates the angle between the two vectors.

- Given two vectors, calculate their cross-product, which calculates a 3rd vector that is perpendicular to both of the original two vectors.

Note that it does not make physical sense to multiply or divide two vectors together.

A JavaScript Vector Object¶

Vector representation and manipulation are fundamental elements of any WebGL

program. This functionality should be implemented once and then used as needed.

The example WebGL program below allows you to inspect a JavaScript class called

GlVector3. Please study the code and note the following about

the GlVector3 class. (Hint: Hide the canvas.)

- An object of type

GlVector3does not store a vector. It is a collection of vector operations. It adds one new “class” to the global address space,GlVector3, and defines 13 functions that perform standard vector operations.

- Examine the

self.create()function to see that a vector is stored as aFloat32Array.

- Most of the member functions do not create new vectors; they operate on

vectors that already exist.This is by design to minimize garbage collection.

- The functions are implemented for speed with minimal or no error checking.

Some examples of JavaScript class definitions. Ignore the functionality and exam the structure and syntax of the class definitions.

Animate

Every WebGL program in this textbook uses the GlVector3 class to

create and manipulate vectors.

Glossary¶

- vector

- a direction in relationship to a frame of reference.

- absolute direction

- a direction that is the same regardless of your current position or orientation (e.g., north or south).

- relative direction

- a direction that changes if your current position or orientation changes (e.g., left or right).

- vector magnitude

- the length of a vector

- normalize

- modify a vector to make its length one unit, but keep its direction unchanged.

Self Assessment¶

-

Q-72: You want to represent a direction that starts at location (2,3) and goes in the direction of location (4,2). Which of the following represents such a direction?

- <2,-1>

- Correct. The direction is 2 units down the x axis and then -1 units down the y axis.

- (2,-1)

- Incorrect. This is a location, not a direction.

- <-2,1>

- Incorrect. The offset between the starting and ending points are correct, but in the opposite direction.

- (-2,1)

- Incorrect. This is a location, not a direction.

-

Q-73: What is the difference between (3,4) and <3,4>?

- (3,4) is a location. <3,4> is a direction.

- Correct. Locations and directions are very different and behave very differently when manipulated.

- (3,4) is a direction, while <3,4> is a location.

- Incorrect. The notation is backwards. (3,4) is a location. <3,4> is a direction.

- They represent the same thing.

- Incorrect. They are not the same thing. Locations and directions behave very differently when manipulated.

- (3,4) goes in positive direction, <3,4> goes in the negative direction.

- Incorrect. This answer makes not sense! What does positive direction even mean?

-

Q-74: Which of the following vectors represent the same direction? (Hint: draw a visual picture of the vectors.) (Select all that apply.)

- <1,2>

- Correct. There is another vector in this same direction.

- <3,6>

- Correct. There is another vector in this same direction.

- <2,5>

- Incorrect. This vector has a unique direction among the 4 vectors.

- <2,1>

- Incorrect. This vector has a unique direction among the 4 vectors.

-

Q-75: A vector defined by 2 distances, <dx,dy>, is …

- an absolute direction.

- Correct. A vector defined by <dx,dy> is an absolute direction. It does not define a reference point from which to start.

- a relative direction.

- Incorrect. A relative direction must define a starting point and the <dx,dy> vector definition only gives a direction.